Diane Vautour,

History Teacher

Diane Vautour is a history teacher with 20 years of teaching experience. She currently teaches at an all-female public secondary school under the Toronto Catholic District School Board. The student body at her school is predominantly white, but it has become more diverse in recent years, with an increasing number of Filipino students. Teaching at an all-female school, Diane emphasizes role plays and simulations to examine historical events from the perspectives of women and other marginalized groups. In the Catholic school context, Diane also incorporates discussions about Catholicism by emphasizing character development and active citizenship. Diane strives to integrate Catholic history into the broader narrative of Canadian history.

Loretto Abbey Secondary School

Toronto, Ontario

Civic Engagement

Diane runs a program called the Youth and Philanthropy Initiative, which is designed to engage students in civic action. The program challenges students to investigate social issues in their city, connect with local charities, and advocate for causes they believe are pressing. Over a four-month period, students research social problems, examine historical root causes, and partner with local organizations. They then present their findings and compete to win grants for their chosen charities.

Diane explains the impact of this project: “For some students it’s a struggle, but it’s like they get to actually talk to people doing the work, they get to go visit a charity or organization and see the actual reality in the city.”

In history class, Diane focuses on empowering students, especially young women and newcomers, by highlighting both major historical events and smaller, relatable stories. The aim is to help students understand their potential as “history makers” and develop their “historical agency.” Diane stresses the importance of teaching students about power dynamics and privilege, encouraging those with advantages to become genuine allies. By connecting historical trends to current civic engagement, she hopes to inspire students to recognize their role in shaping society and to take action on issues that matter to them.

Historical Thinking

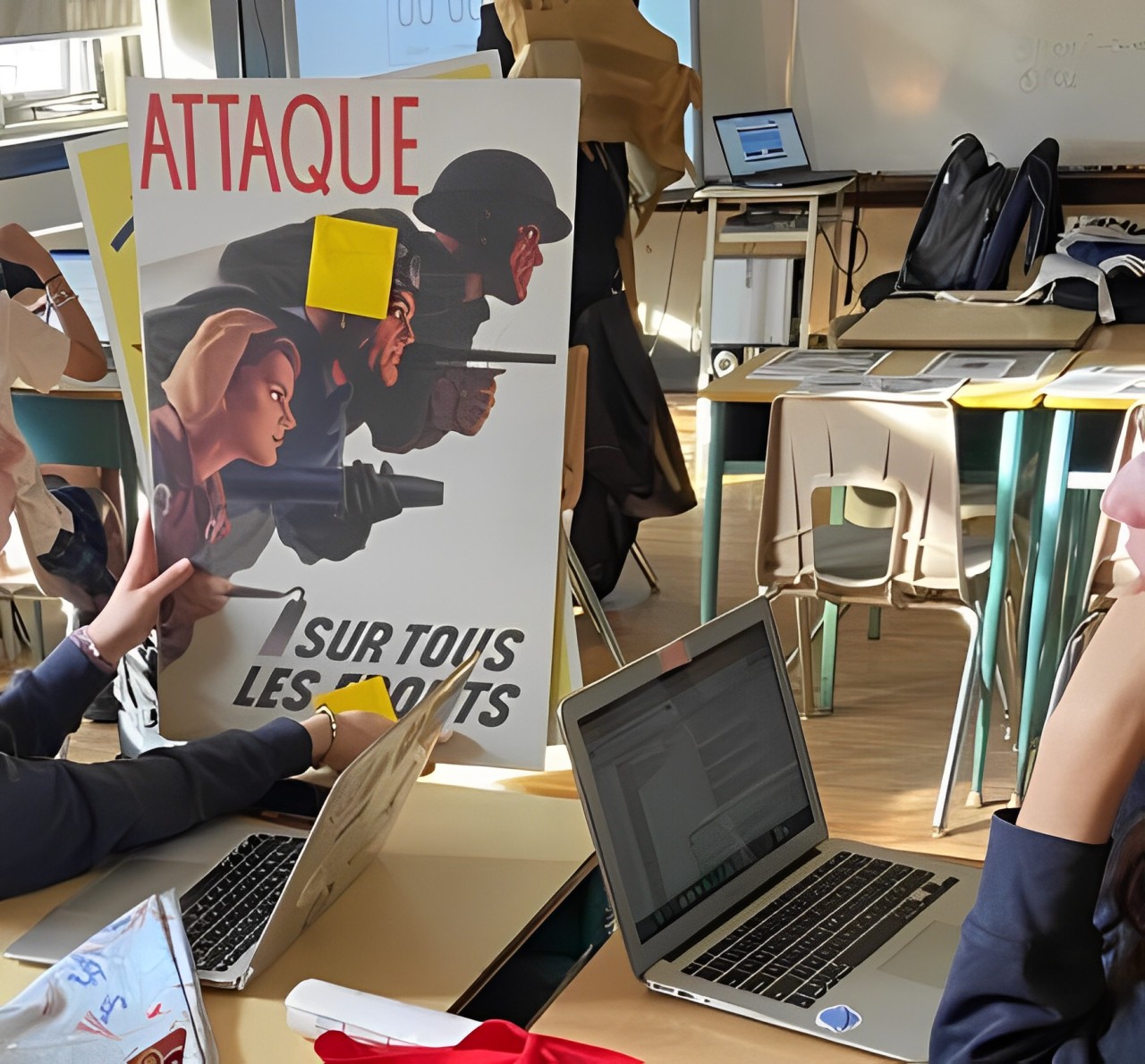

Diane discusses her approach to teaching historical thinking by emphasizing the importance of understanding different perspectives and avoiding presentism. She describes a favourite lesson that challenges students to analyze various reactions to World War I or II from diverse viewpoints. She explains, “I try to teach students about people’s reactions to war. And try to get a wide variety regionally, linguistically, you know, gender, sex, power, and socioeconomic class, like all these kinds of reactions, either to World War One or World War Two.”

In this lesson, the students examine primary sources such as newspaper articles or interviews, conducting a worldview analysis to understand the perspective of historical figures. Diane starts the activity by having students analyze report card comments, encouraging them to consider the teacher’s worldview and beliefs about education. She then applies this approach to historical contexts, asking students to interpret reactions to war from various perspectives, such as “some small-town kid versus somebody sitting in Toronto whose, you know, parents are British and fought in the Boer War.”

Diane stresses the importance of understanding historical context to avoid simplistic criticisms or presentism. She notes, “It’s not to condone it. But sometimes we get into criticism without context. And then we get into presentism. And then it’s just like, we’re not doing the real thinking on history.”

Indigenous Knowledges

Diane led the writing of Ontario’s 2018 revised curriculum that incorporated Indigenous expectations, and she reflects on her unique position: “I was hired and when I walked in that room, I was like, ‘Why am I the person writing this?’ But it’s only because I had the writing experience, but I was the only white person on the team.”

Despite her extensive experience in curriculum development, Diane acknowledges limitations in her classroom practice. She notes that while Indigenous history forms a significant part of her instruction across various courses, experiential learning opportunities such as land-based education or working with Elders are still lacking in her context.

She also observes that her school board’s approach to Indigenous education “seems to be still at the tokenistic level,” often limited to occasional guest speakers. However, she has incorporated projects like “Project of Heart” and organized field trips to former residential schools to engage students with Indigenous issues.

Co-created by Diane Vautour and Christine Cheng