Sarah Bruckschwaiger,

High School Social Studies Teacher

Sarah Bruckschwaiger teaches Social Studies for grade 10-12 students and has been teaching for seven years. She teaches at Maani Ulujuk School, a secondary school in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. As Sarah explained, about 80% of the people in Rankin Inlet are Inuit, while 20% are people from outside of Nunavut and newcomers to Canada. While most of her students speak English as their first language, many of their parents and grandparents speak Inuktitut at home. Sarah explained that while traditional Inuit culture is very important in Rankin Inlet, her students are also interested in mainstream pop culture and media. In addition, intergenerational trauma affects many families in Rankin Inlet and Nunavut more broadly, which plays a significant part of her students’ lives.

Maani Ulujuk School

Rankin Inlet, Nunavut

Teacher Education

When Sarah came to Nunavut from Ontario, she was afraid of failing her students. “I was a total outsider,” she said. “It was a massive undertaking to try and educate myself so that I could be in a position to even be a teacher without feeling like a joke.”

Seven years into her career, Sarah said that fear has been replaced by a motivating anxiety fueled by a desire to best serve her students and the Rankin Inlet community.

“There is always another book you can be reading, there’s always more you can be learning, there’s always another Elder that will tell you something that’s going to blow your mind,” she said.

Sarah emphasized the need for teachers coming from southern regions to commit to being lifelong learners, especially when it comes to local history, language, and culture. “I didn’t want to be the colonial white settler who’s failing these kids who deserve to know about their history and be proud of their traditions.”

Although Sarah’s teacher education program did not effectively prepare her to teach in Nunavut, she said, the “incredible foundation for how to think about what I was doing as a settler teaching in an Indigenous context gave me the theoretical foundations for how to approach teaching in a way that was equitable, culturally relevant, diversified, and inclusive.”

Met with a mix of her own professional development along with the theoretical teaching practices from her teacher education, Sarah is committed to best serving her students in her teaching.

Curriculum & Resources

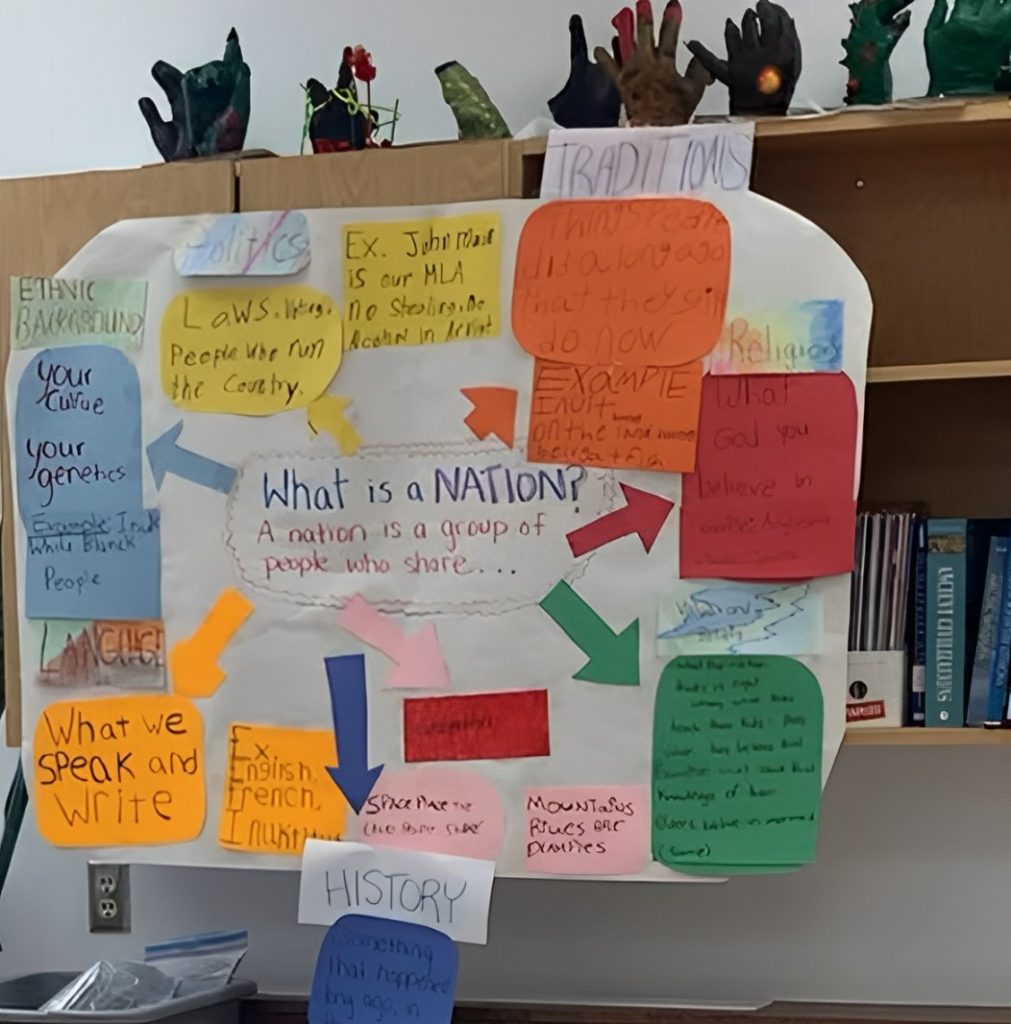

The mandatory grade 10 Social Studies course in Nunavut is delivered using materials that are based on Inuit history and culture and developed with new and itinerant teachers in mind. Whereas many senior high school courses in Nunavut are accredited by, or adapted from, the Alberta curriculum, grade 10 Social Studies is an exception. “Since Nunavut’s creation, one of its stated goals is to create all its own curriculum, and that has been extremely slow moving. But a few courses are created in Nunavut, and wonderfully enough grade 10 Social Studies is one of them.”

Teachers are provided with handbooks and videos that outline the detailed content and activities to be used in their classrooms. Sarah describes how these materials are prepared intentionally for new or itinerant teachers—predominantly non-Indigenous teachers with no previous knowledge of Nunavut—so they can teach in a locally-appropriate way.

While teachers must still adapt these materials for the literacy levels and needs of their students, Sarah finds that the activities work well with students. Apart from being engaging, the course situates Inuit students in their own history by outlining: “the history of the Inuit people and their tradition, the creation of Nunavut (which is the largest Indigenous land claims agreement in the world), and a deep sense of rightfully earned pride.”

Teaching & Learning

Sarah has found that one of the best ways to teach history in Rankin Inlet is through dramatic narratives. As she explained, “I think because there’s such a strong oral storytelling tradition in Nunavut, and because Inuit have a wonderful sense of humour, and a wonderful ability to tell a good story, I’ve found that the best way to teach history is by using similar storytelling techniques.”

Unlike many of her former students in southern provinces, Sarah’s Nunavut students don’t seem engaged by descriptions of military tactics, and don’t have much interest in watching movies in class. Instead, she said, they learn best through her animated retellings of the lives of people from the past, like Napoleon.

“I’ll say things like, ‘Can you believe it? They put him on his own private island with his own chef, and any of his friends he wanted could come with him. But was he happy on his island? No! Because he’s obsessed with being in charge, right?’ And then they’ll say, “Oh so, what did he do? Did he try to escape?’ And it goes from there… they are completely wrapped up in the story, and they really retain information that way, because the oral tradition is such a big part of their culture.”

Co-created by Sarah Bruckschwaiger, Kyle Raymond, and Dr. Heather McGregor