Jean-François Gosselin,

Social Science teacher

Jean-François Gosselin is a social science teacher at Marcelle-Mallet secondaire privée, a private high school in Lévis, Quebec. He mainly teaches history courses to students in grades 7 to 11. This private institution’s student body is socioeconomically diverse, ranging from middle- to high-income, but it does not select students based on academic achievement. Most students are from Quebec, but in recent years the school has seen a slight increase in the number of international students, who now represent less than 10% of the student body. This growing diversity enriches the educational experience, bringing new perspectives to an already innovative academic environment. The school is also distinguished by its advanced integration of technology, with every student having access to a laptop, and by the management’s active support for pedagogical and technological innovation.

Marcelle-Mallet secondaire privé

Lévis, Québec

Indigenous Knowledge

In Jean-François’s view, the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge into the teaching of history is based on a conscious approach that highlights the diversity of Indigenous perspectives, despite the limitations created by school curricula.

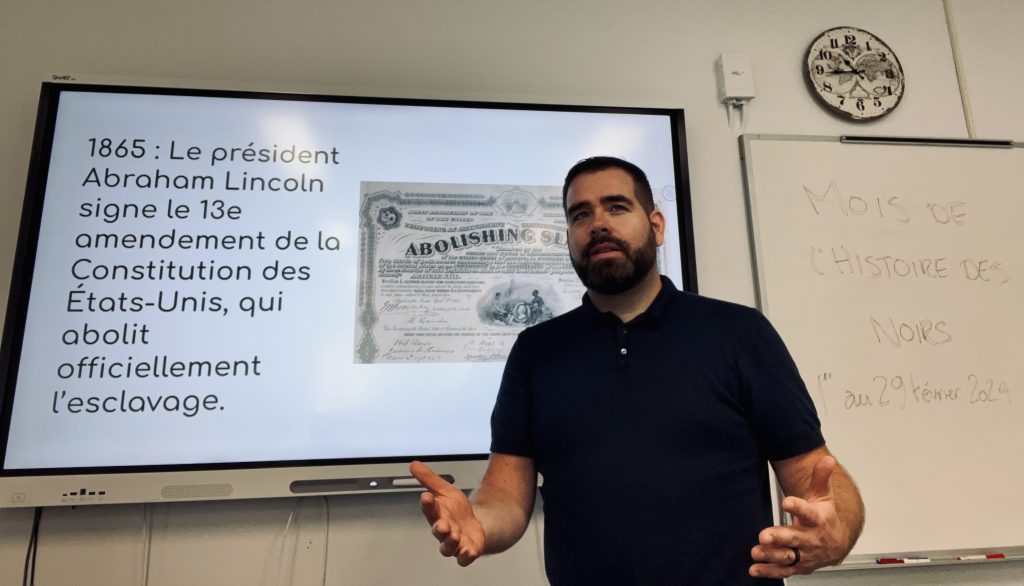

Exploring the complexity of his personal and professional identity, Jean-François discusses his sensitivity to diversity and how it influences his approach to teaching. He states, “I consider myself to be someone who’s quite sensitive to the subject of diversity, so I try to include it, even if it’s not in the curriculum,” referring to his initiative to introduce extra-curricular elements, such as facts about Black History.

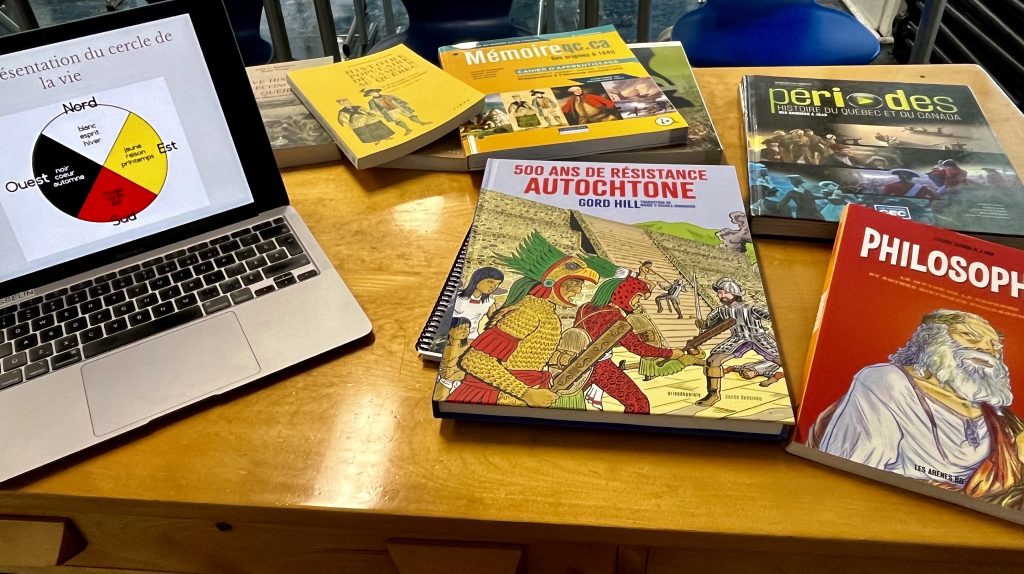

Jean-François also strives to expand the course content to include Indigenous realities seldom addressed in official curricula, emphasizing the importance of these issues in the teaching of Quebec and Canadian history up to 1840. He points to the influence of recent movements, such as Idle No More and the residential school tragedy, on public sensitivity in this regard. “I try to show a certain sensitivity to it, but obviously when you have a curriculum to follow […] it’s there, but [only] to a certain extent,” he explains. This reflects the tension between adherence to the curriculum and the need to incorporate broader, more current perspectives, highlighting a disconnect between school curricula and contemporary social realities.

Civic Engagement

By immersing himself in his students’ historical past, Jean-François explores methods for engaging young people in civic reflection, despite the challenges associated with the temporality of the subjects covered.

Jean-François highlights the importance of civic engagement in teaching history to Secondary 3 students. He admits that “it’s a bit more difficult, because we’re so far in the past,” but he uses methods like ephemerides at the beginning of the course to make the connection between past and present. These moments give students the opportunity to discuss historical objects and take a position on them, which he sees as a form of civic engagement.

Inspired by the works of Carla Peck from the University of Alberta, Jean-François encourages his students to make connections and reflect on historical positions. For example, he asks them to analyze the royal government in New France, or to select historical artifacts and explain their cultural and historical significance. These activities lead them to explain the relevance of these objects for a museum collection. Jean-François firmly believes that although these activities are rooted in the past, they are an integral part of civic education, helping to develop in young people a curiosity and empathy that prepares them to better understand and participate in the modern world.

Co-created by Jean-François Gosselin, René Salem and Gabriel Masi