Dr. Lyndze Harvey

University of Victoria

Dr. Lyndze Harvey, an Assistant Teaching Professor of Social Studies and Philosophical Foundations at the University of Victoria, leads social studies curriculum for elementary and middle years, and consults on pre-service teacher course selection. As an out queer settler woman, she recognizes the profound political influence of her identities on her teaching. Dr. Harvey is dedicated to deconstructing coloniality within her educational practices.

Curriculum in Context

Working on the unceded territories of the the lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) speaking peoples, Dr. Harvey understands her work within an existing social studies curriculum tied to the land and reconciliation efforts. She observes that while most of her students are from B.C. and have some familiarity with this curriculum, the training for educators in this area has been insufficient.

Dr. Harvey observes that many students “arrive with still very basic or minimal knowledge about coloniality and are not really politically informed.” She also points out that the majority of her students are white, cisgender women. Many incoming pre-service teachers also believe they can remain politically neutral in the classroom. Dr. Harvey strives to help her students unlearn this, and asserts that “teaching is inherently political,” especially when shaping future citizens. The curriculum itself requires political engagement, aiming to “educate informed citizens who are able to think critically in a pluralistic democracy.”

From Theory to Practice: Curricular Goals in Action

Dr. Harvey’s approach as a pre-service social studies educator is shaped by this tension between political neutrality and the curriculum’s call for critical engagement. “My pedagogical approach is to unsettle, to make space for discomfort, and to walk beside them in that discomfort,” she states, aiming to build students’ confidence in critically engaging with the past and present.

One method she employs is teaching students to critically examine historical narratives by identifying “S.W.A.K’s” (“stories we all know”). Dr. Harvey guides students to recognize these inherited narratives and assumptions about topics like gender and ethnicity. “Our job,” she explains, “is to be able to see the story we all know and help students see that story.”

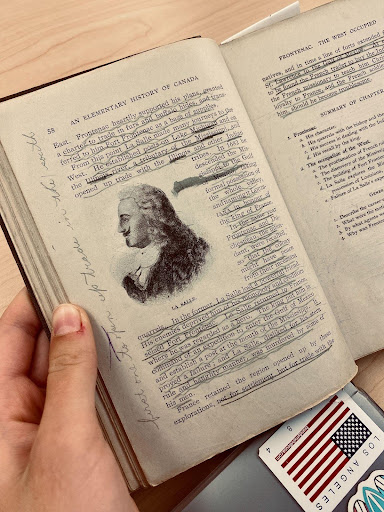

To illustrate this, Dr. Harvey has students investigate historical textbooks from the University of Victoria library, tasking them with finding “S.W.A.K’s.” Students have observed problematic narratives regarding Indigenous children, women, and more.

Dr. Harvey and students looking for “S.W.A.K’s” in historical textbooks at the University of Victoria library. Photo provided by Dr. Harvey.

This activity also highlighted silenced histories. For instance, a student of Chinese ancestry found no mention of their family’s contribution to the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in the textbooks, despite the building of the CPR being described as foundational to Canada’s history. This sparked meaningful discussions about immigration stories and the silencing power of “S.W.A.K’s.”

This work culminates in a “Resist a Resource” activity, where students choose a contemporary resource (e.g. textbooks, CBC Radio, maps, clocks) and analyze, as Dr. Harvey describes, “how coloniality might be baked into it, how it tells a story we all know, or reinforces one, or how it might even upset one.” This exercise helps students see the interconnectedness of histories and their influence on present narratives.

Through this, Dr. Harvey fosters historical consciousness, which for her means to “understand the past more holistically, and understand the interconnectedness and interdependence of all of us with each other, with ourselves, with the more than human, and with ideas.” By identifying “S.W.A.K’s” in both past and present, she helps students connect with history and its ongoing impact.

Page from a historical Canadian history textbook from the University of Victoria library. Photo provided by Dr. Harvey.

Navigating the Complexities of Teacher Preparation

Dr. Harvey acknowledges the complexities of preparing pre-service teachers to engage with the past, citing students’ varied foundational knowledge and limited instructional time. “My students are often looking for a list of what to do, and that’s not what social studies is about. I really try to undo some of that,” says Dr. Harvey.

To foster critical conversations, Dr. Harvey prioritizes front-loading information and vocabulary about concepts like microaggressions and non-violent communication. “A lot of them are afraid to use the language. They’ve heard it, but they’re afraid to use it,” she observes, noting that this preparation creates a safer, richer, environment for discussion.

To address the challenge of disengagement, Dr. Harvey cultivates a classroom culture of intellectual equality where student expertise and interests are honoured. She strives to model openness to not having all the answers, and to embracing the discomfort of our work as educators. She hopes to put pre-service teachers on a path where they “can continue to dismantle the stories we all know and coloniality, because these are things that we have committed to in B.C.”

Co-created by Dr Lyndze Harvey and Jessica Gobran